PREVIOUSLY: MOULIN ROUGE!

A war film released in 2001, Black Hawk Down, directed by Ridley Scott and based on the nonfiction book of the same name by Mark Bowden, chronicles the events of the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia in 1993.

First of all, read the book. Holy shit, read the book. I didn’t hate this movie or anything, it was fine, but I couldn’t stop thinking the entire time about how it utterly paled in comparison to the book because the book is as good as it is. Read the book.

Unfortunately, due to the differences between a dramatized film and a nonfiction book, some of the book’s strengths must by necessity fall to the wayside. The book covers so much. It has the time and ability to focus on one soldier at a time and relay his story, his thoughts and emotions in extreme detail. It also covers some of the aftermath of the battle; including more of the captivity and subsequent safe return of Chief Warrant Officer Mike Durant, the families of the soldiers learning that their loved ones have been killed in action, a discussion of what exactly went wrong, and how the battle affected the U.S. and U.N.’s international policies going forward and some of the ripple effects this likely caused. And, quite crucially, it takes the time to periodically switch to the point of view of Somalis, militia members and civilians alike. These passages, although extremely brief compared to the American side of the narrative, manage to pack a wallop. They provide context and nuance that the movie ends up sorely missing. From the Somalis’ point of view, even from those who are relatively sympathetic to the Americans, it makes perfect sense why there is so much anger toward the American presence, why civilians joined the fight against them, and one of the reasons this ended up escalating the way it did.

The movie is technically impressive and feels very realistic and visceral in some scenes, particularly in the depiction of the wounded. But otherwise, it just sort of fell flat for me. I recognized these men and some of the vignettes from the book, but I couldn’t help but think that I would not care about them as much as I did if I hadn’t read the book, even though I know this was based on true events, because the film gave me so little to emotionally latch onto. The film had to drastically cut the number of men compared to the book, and only focus on a handful of them because of time and scope restraints. But the men as portrayed in the film have so much detail filed off that they could easily have been exchanged with each other or been played by a different actor in every scene, and I couldn’t imagine it making much of a difference.

Another area lacking in nuance compared to the book is the question: What caused this and who is to blame? Mark Bowden answers this question with incredible grace and finesse, and as much objectivity as is possible for a human to have. The truth of the matter is that it’s complicated, as is nearly always the case when it comes to global politics and war. The answer he more or less ends up arriving at is that everyone is to blame and no one is to blame. He manages to instill sympathy in the reader for every single person involved with this horrible affair on all levels, and checks the reader if they ever start to imagine what they could’ve done better. The Battle of Mogadishu was a compounding series of errors, a colossal and tragic fuck-up, that accomplished nothing except perhaps very briefly causing the U.S. to reevaluate its global interventionist strategy and question whether we really did know better than the people who actually live in these countries. But of course, even that doubt didn’t last long. By the time the movie came out, the doubt was already gone.

There’s a critical consensus, I believe, that most war movies, even the ones that set out to be antiwar, inevitably end up accidentally making war look cool. I don’t think Ridley Scott set out to make a propaganda movie. I do know he had to play nice with the Department of Defense if they were going to cooperate with the making of this film and allow the use of their special equipment, including their Black Hawks. “Black Hawk” is two-thirds of the title. If there are no Black Hawks, there is no movie. And sure enough, the movie got made and the Department of Defense is there receiving a “special thanks” in the end credits. And it shows.

As I said, the scenes of wounded soldiers are horrifying. But those, in all, take up a very small portion of screen time. Mainly, it’s American soldiers shooting at “militia members.” (In the book, it repeatedly made it very clear that the Americans became so panicked that they also indiscriminately shot at civilians.) There are fictionalized moments that make the Americans look more competent and awesome than they were. And every so often, the movie goes into slow-motion. The most egregious use of this is in the final stretch of the Mogadishu Mile, in which the last group of soldiers had to race on foot, unprotected by the convoy, to the rendezvous point deeper within the city before finally loading up and pulling out. The movie takes some major artistic license by depicting the soldiers running all the way to the safety of the soccer stadium held by the Pakistanis. That, while inaccurate, I don’t necessarily have a problem with. It’s more visually dramatic, they’re still running to safety and it streamlines events a little more, okay, fine. The issue I have is that it adds a sequence of three young boys joyously running ahead of the wounded and exhausted American soldiers, smiling back at them and urging them on to shelter, as a crowd of Somali civilians stands on either side applauding. This is a movie that only barely depicted the whole reason the Battle of Mogadishu was burned into the cultural consciousness at all in the first place–the desecration of the corpses of American soldiers at the hands of enraged Somali mobs–but they did decide to depict this entirely fictional scene of happy and grateful Somalis cheering on the invading Americans the entire city has just spent the last twenty-four hours trying to kill after at least several hundred of their own, including women and children, have been mowed down by said Americans…hm. Interesting. Especially compared to how differently the Mogadishu Mile is described in the book:

They all kept running, running and shooting through the brightening dawn, through the crackle of gunfire, the spray of loose mortar off a wall where a round hit, the sudden gust of hot wind from a blast that sometimes knocked them down and sucked the air out of their lungs, the sound of helicopters rumbling overhead, and the crisp rasp of their guns like the tearing of heavy cloth. They ran through the oily smell of the city and of their own bodies, the taste of dust in their dry mouths, with the crisp brown bloodstains on their fatigues and the fresh memory of friends dead or unspeakably mangled, with the whole nightmare now grown unbearably long, with disbelief that the mighty and terrible army of the United States of America had plunged them into this mess and stranded them there and now left them to run through the same deadly gauntlet to get out. How could this happen?

Mark Bowden, Black Hawk Down

Though production was completed before, Black Hawk Down was released shortly after 9/11, and it makes a lot of sense that it was so successful in its wake. While it is possible to have sympathy for what the soldiers experienced, it is also possible to look at it from the Somali side and see the bigger picture. The book makes you uncomfortable, and it wants you to sit with that. It wants you to realize that massive harm was done, and yet there are no easy answers about what could have been done differently. The film only bothers to humanize the Americans and stops there. That’s it. This is the most “Don’t ask questions, just shut up and Support Our Troops” movie I’ve ever seen.

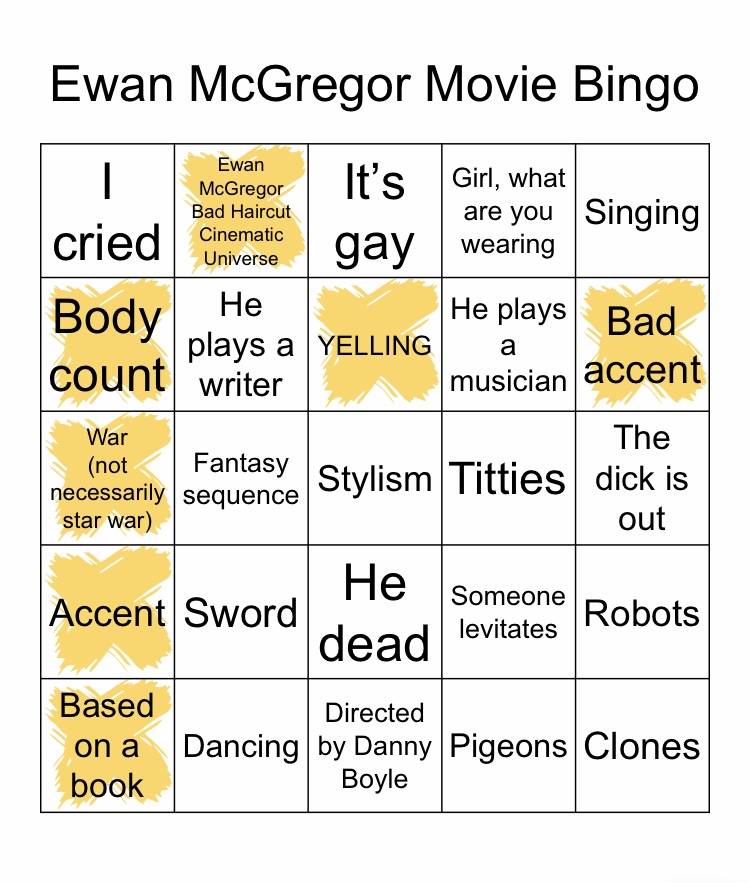

One more thing to note, aside from the fact that no Somali actors played the Somalis, and the frankly disconcerting number of British guys playing Americans (almost no one’s r‘s sound right,) is Ewan McGregor’s character, Grimes. Bless him, Ewan’s trying for an American accent again, and it’s still not great. It’s possibly the worst fake American accent of all the kind of bad fake American accents.

There is not a man named “Grimes” in the book. Instead, we have “Stebbins,” the clerk, who makes the other soldiers coffee and that’s mostly it. That is, until Specialist Dale Sizemore is wounded just before the raid and Stebbins is called to go in his place, forced to step up and find courage he didn’t know he had. Given these similarities, it’s clear that the fictional Grimes is based on the real Stebbins. So why the name change? No one else’s names got changed. Why him?

Well. (And to be fair, this wasn’t mentioned in the edition of the book I read either, even though it was an updated one that came out after the movie.) Staff Sergeant John Stebbins, who was awarded the Silver Star after the Battle of Mogadishu, pled guilty to raping his six-year-old daughter in 1999 and was sentenced to thirty years in prison. He reportedly only served part of that sentence, and was released in 2018. Someone claiming to be him can frequently be found in comment sections and message boards that discuss this turn of events, cussing out and threatening the people who find this unexpected development horrifying.

Reasons given for the name change differ. Some involved with the production claimed it was their own creative decision. The more widely accepted version is that the Department of Defense wanted to keep Stebbins’s inspiring story to urge more nerds to enlist, but didn’t want anyone going home after the movie to look him up and find out that he was, at the time of the movie’s release, in prison for raping his own child. So Stebbins becomes Grimes and he’s the comic relief to the point the coffee schtick is eyerollingly forced and he’s played by Obi-Wan Kenobi and he’s a war hero and nothing else. It’s grim.

Black Hawk Down is a book I found incredibly difficult to read, but I also couldn’t put it down. I think it should be required reading. It manages to tell a confusing, chaotic, painful, brief chapter in American and Somali history, and it tells it with clarity, sympathy, depth and nuance. It’s a book so detailed and so good that no movie version could stand up to it, and in my mind, Ridley Scott’s attempt certainly doesn’t.